When Empire Met Reality in the Tanganyikan Bush

A Feature Story on Colonial Hubris and Agricultural Catastrophe by Anthony Muchoki

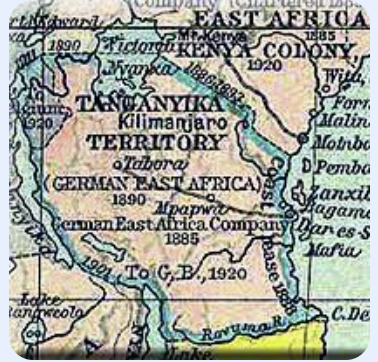

In the scorching heat of January 1947, Major-General Desmond Harrison stood atop a Land Rover, surveying the vast Tanganyikan bushland stretching endlessly before him. Armed with little more than British optimism and a government checkbook, he was about to lead one of the most ambitious—and ultimately disastrous—agricultural projects in colonial history.

The Groundnut Scheme, as it came to be known, would pour £49 million (equivalent to over £1.5 billion today) into the East African soil, only to harvest humiliation, mechanical wreckage, and barely enough peanuts to fill a corner shop. This is the story of how post-war Britain’s desperate need for oils and fats led to an agricultural catastrophe that became a byword for colonial incompetence.

The Post-War Dream

Britain in 1946 was broke, hungry, and still rationing butter. The war had ended, but victory tasted bitter when served on empty plates. The nation desperately needed oils and fats—for margarine, soap, and industrial uses. Enter the United Africa Company with a seductive proposal: why not transform “useless” African bushland into vast groundnut plantations?

The plan was breathtaking in its ambition. Three and a quarter million acres of Tanganyikan bush would be cleared and planted with groundnuts. Modern machinery would revolutionize African agriculture. Britain would get its oils, Tanganyika would get development, and everyone would prosper. What could possibly go wrong?

Minister of Food John Strachey championed the scheme with evangelical fervor. “This is not just about groundnuts,” he declared in Parliament. “This is about bringing the twentieth century to Africa, about showing what British expertise and machinery can achieve.”

The Wakefield Mission, sent to survey the proposed areas, spent a mere nine weeks on the ground—during the dry season. Their glowing report failed to mention that they had barely scraped the surface of understanding the land they proposed to transform.

The Three Fronts of Failure

Kongwa: The Heart of Darkness

Kongwa, in central Tanganyika, was chosen as the scheme’s headquarters and flagship site. The first challenge came immediately: clearing the bush. The planners had imagined soft African soil yielding easily to British steel. Instead, they encountered the infamous “mbuga”—rock-hard clay that shattered plows and broke the spirits of machines and men alike.

The scheme’s managers had purchased surplus military equipment at bargain prices, including Sherman tanks fitted with ship anchor chains for bush clearing. The sight of these war machines grinding through the African bush, chains flailing wildly, became an enduring image of colonial absurdity. The tanks, built for European battlefields, broke down constantly in the African heat and dust.

Local Gogo people, who had farmed this land for generations, watched with a mixture of amusement and horror. “They brought iron elephants to fight the earth,” recalled one elder years later. “But the earth always wins.”

The soil at Kongwa, when finally cleared, proved to be largely unsuitable for groundnuts. The clay hardened to concrete in the dry season and became an impassable quagmire when the rains came—if they came at all. The first harvest yielded 2,000 tons of nuts from 50,000 acres—a pathetic return that wouldn’t have fed a small English town, let alone helped solve a national crisis.

Urambo: The Western Wilderness

Urambo, in western Tanganyika, presented different challenges. Here, the scheme encountered the fierce resistance of baobab trees, some centuries old, their massive trunks defeating every attempt at removal. Dynamite was eventually used, turning agricultural development into something resembling warfare.

The labor shortage was acute. The scheme’s planners had assumed abundant local labor, but the wage offers were insulting compared to work available on established sisal plantations or in the mines. Those who did come often left after seeing the working conditions. Housing was inadequate, food supplies erratic, and the promised development benefits nowhere to be seen.

One British agricultural officer wrote in his diary: “We are trying to impose industrial agriculture on a land we don’t understand, with machines that don’t work, using methods that don’t apply. The Africans think we’re mad, and I’m beginning to agree with them.”

Nachingwea: The Southern Struggle

In the south, Nachingwea initially showed more promise. The soil was better, rainfall more reliable. But even here, the scheme’s fundamental flaws emerged. The port facilities at Mtwara, built at enormous expense to export the expected groundnut bounty, became a monument to misplaced optimism. The planned railway line was never completed, leaving expensive infrastructure stranded like a bridge to nowhere.

The human cost at Nachingwea was particularly stark. Thousands of workers were recruited from across Tanganyika and beyond, promised good wages and prosperity. Instead, they found themselves in camps with inadequate sanitation, limited medical care, and food supplies that frequently ran out. Disease outbreaks were common. Many workers simply abandoned the scheme, walking hundreds of miles home with nothing to show for their labor.

The Machinery Graveyard

Perhaps nothing symbolized the scheme’s failure more than the machinery graveyards that dotted the three sites. Brand new tractors, combines, and bulldozers—much of it unsuitable for tropical conditions—littered the landscape like the bones of mechanical dinosaurs.

The scheme had imported 500 tractors and 300 bulldozers, most of which were dead within months. Spare parts took months to arrive from Britain. There were no repair facilities adequate for the scale of breakdown. Dust clogged engines, tropical humidity corroded electrical systems, and the brutal landscape destroyed undercarriages designed for European fields.

A visiting journalist in 1949 described the scene at Kongwa: “It looks like the aftermath of a great battle—which in a way, it was. A battle between British industrial confidence and African environmental reality. Africa won.”

The Human Toll

Behind the financial figures and mechanical failures were human stories of disruption and suffering. Traditional farming communities were displaced. The Gogo people at Kongwa lost grazing lands their cattle had used for generations. Labor migrants who had left their families for promised wages returned home empty-handed and bitter.

European staff, too, paid a price. Families recruited to this “great adventure” found themselves in isolated camps, struggling with heat, disease, and the growing realization that they were part of a massive failure. Alcoholism was rampant. Marriages collapsed. Several suicides were quietly covered up.

Dr. Margaret Read, an anthropologist who visited the scheme, wrote: “This is not development; it’s destruction. Destruction of land, of traditional systems, of faith in colonial promises, and ultimately, of the very idea that Europe knows best for Africa.”

The Political Earthquake

Back in Britain, the scheme became a political scandal. The Conservative opposition seized on it as evidence of Labour government incompetence. Winston Churchill called it “the groundnuts fiasco” in a speech that helped damage Labour’s reputation for economic management.

By 1949, it was clear the original scheme was doomed. Alan Lennox-Boyd, visiting as a Conservative MP, reported scenes of “mechanical chaos and agricultural disaster.” The government tried to rebrand it as the “Overseas Food Corporation,” shifting focus from groundnuts to general agricultural development, but the damage was done.

In January 1951, the scheme was officially abandoned. The final tally was devastating: of the planned 3.25 million acres, only 50,000 had been cleared by the scheme’s end. Total groundnut production was less than 10,000 tons—a fraction of what a single good farm in America might produce. The financial loss of £49 million was enormous for cash-strapped post-war Britain.

Lessons Written in Red Dust

The Groundnut Scheme’s failure was not just bad luck or poor execution—it was a fundamental misunderstanding of place, people, and purpose. The planners never truly consulted local farmers who had generations of knowledge about the land. They ignored ecological realities in favor of mechanical solutions. They treated Africa as an empty space waiting for European expertise, rather than a complex environment with its own logic and limitations.

Environmental scientists would later identify multiple factors the scheme had ignored: irregular rainfall patterns, soil types that varied dramatically even within small areas, plant diseases unknown in Europe, and an ecosystem that fought back against industrial-scale monoculture.

The scheme also revealed the fatal flaw in colonial development thinking: the assumption that what worked in Europe would work in Africa, that machinery could overcome nature, that top-down planning could ignore local knowledge.

The Groundnut Ghost Towns

Today, visitors to Kongwa can still see remnants of the scheme. Rusted machinery parts surface during plowing seasons like archaeological artifacts of failed ambition. The grand headquarters building, once buzzing with colonial administrators, serves as government offices for the small town that grew from the scheme’s infrastructure.

Some good did emerge from the disaster. Roads built for the scheme opened up previously isolated areas. Some cleared land was eventually used for other crops by local farmers—though using their traditional methods, not European industrial agriculture. The port at Mtwara, though underutilized for decades, eventually found purpose in other developments.

The railway that was supposed to connect Nachingwea to the port was never built, but its surveyed route became a road that locals still call “the groundnut road”—a name spoken sometimes with irony, sometimes with anger, always with memory.

Echoes in Modern Development

The Groundnut Scheme’s failure resonated far beyond Tanganyika. It became a cautionary tale cited in development studies, a paradigm of how not to approach agricultural transformation in Africa. When Tanzania gained independence in 1961, Julius Nyerere would reference the scheme as an example of colonial exploitation and ignorance.

Yet the lessons were not always learned. Subsequent decades would see other grand agricultural schemes in Africa fail for similar reasons: ignoring local knowledge, imposing inappropriate technology, and assuming that external expertise could override environmental realities.

Modern development theorists point to the Groundnut Scheme as a textbook case of “high modernist” failure—the belief that scientific planning and industrial methods can reshape nature and society without understanding their complexities. James C. Scott, in his influential book “Seeing Like a State,” uses similar schemes to illustrate how such projects are doomed when they ignore local knowledge and ecological complexity.

The Survivors Speak

In 2001, on the scheme’s 50th anniversary, the BBC tracked down some surviving workers. Mzee Rashidi, who had worked as a tractor driver at Kongwa, remembered: “We knew it would fail. The land was telling us, but the British wouldn’t listen. They had their papers and their machines, but they didn’t have wisdom.”

Elizabeth Thompson, widow of a British agricultural officer, reflected differently: “My husband genuinely believed they were doing good, bringing progress. The failure broke him. He never really recovered from seeing all that effort, all those hopes, turn to dust.”

Conclusion: When Empires Dream

The Groundnut Scheme remains one of history’s most spectacular agricultural failures, a monument to colonial hubris and the dangers of ignoring local knowledge and environmental realities. It stands as a reminder that development cannot be imposed from above, that machinery cannot overcome ecology, and that the earth, as the Gogo elder observed, always wins.

In the grand narrative of decolonization, the Groundnut Scheme played an unexpected role. Its failure helped discredit colonial claims of superiority and competence. If Britain couldn’t even grow peanuts properly, what right did it have to rule?

Today, as the world grapples with new agricultural challenges—climate change, food security, sustainable development—the lessons of the Groundnut Scheme remain relevant. True agricultural development must be rooted in local knowledge, ecological understanding, and genuine partnership, not imposed through foreign expertise and mechanical might.

The red dust of Kongwa, Urambo, and Nachingwea has long since settled, but buried within it are lessons written in rusted machinery and failed harvests: respect the land, listen to those who know it, and remember that hubris, no matter how well-funded or mechanically equipped, is no match for the patient, inexorable resistance of the earth itself.

As one Tanganyikan farmer reportedly told a departing British administrator: “You came to teach us how to grow groundnuts. But you learned that we already knew how. We just didn’t do it your way.”

The Groundnut Scheme ended not with a bang but with a whimper—administrators quietly packing up, workers drifting away, and the bush slowly reclaiming what had always been its own. In the end, it produced more lessons than groundnuts, more humility than oil, and more questions than answers about what development really means and who gets to define it.

Perhaps that, inadvertently, was its most valuable crop.

Author’s Note: This story is based on historical records, parliamentary papers, and accounts from various sources including colonial archives, survivor interviews, and secondary historical analyses. The Groundnut Scheme remains a defining moment in late colonial history and continues to offer lessons for contemporary development initiatives.