Investment blueprint for Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania

The Release of the SAGCOT Investment Blueprint

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania — September 2022

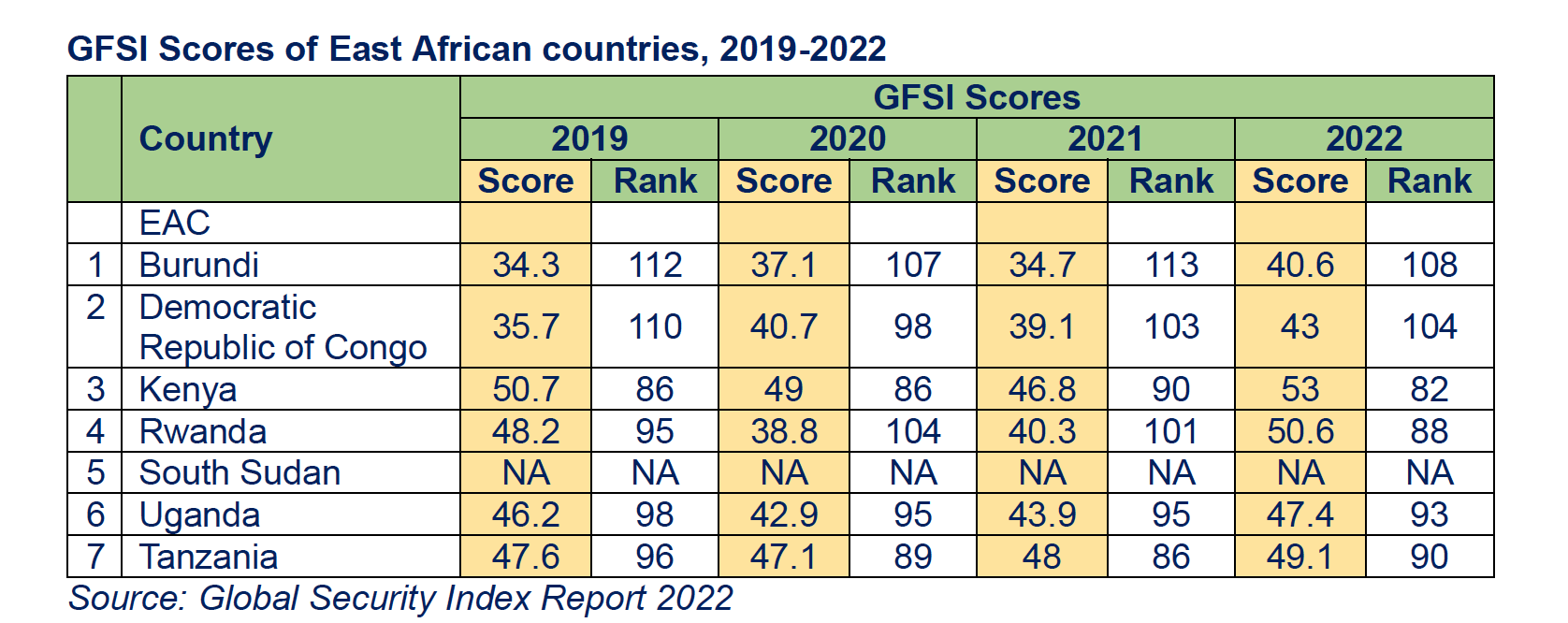

In the heart of East Africa, a quiet revolution has been unfolding across the vast and fertile landscapes of southern Tanzania. A decade ago, in the wake of mounting food insecurity, rural poverty, and underutilized agricultural land, the Government of Tanzania stood at a crossroads. It faced a bold question: Could agriculture—long held as the backbone of the nation—be reimagined to drive inclusive, sustainable economic growth?

The answer was yes. And it came in the form of the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT).

Officially launched at the World Economic Forum on Africa in 2010, and then formalized through the SAGCOT Investment Blueprint in January 2011, the vision gained traction by September 2012 when the groundwork had been laid for implementation. SAGCOT became not just a strategy, but a movement—a unifying framework linking public and private sectors, smallholder farmers, global investors, and development partners in pursuit of a common goal: to turn Tanzania’s southern corridor into a breadbasket for the region.

The blueprint laid out an ambitious plan: catalyze $2.1 billion in private investment, leverage $1.3 billion in public financing, and bring 350,000 hectares into profitable, sustainable production by 2030. And more importantly, do so in a way that would lift two million Tanzanians out of poverty, create 420,000 new jobs, and establish Tanzania as a competitive agricultural exporter on the African and global stage.

Between 17 September 2012 and 4 September 2022, SAGCOT became a living example of what can be achieved through vision, leadership, and collaboration. From the transformation of Kilombero’s rice valleys to the revitalization of Ihemi’s highland horticulture, the corridor evolved into an ecosystem of productivity—complete with agriculture clusters, irrigation schemes, farm-to-market infrastructure, and strong value chains.